In this series of posts, Astrid Bracke writes about the process of moving from disseration to book. She has a PhD in ecocriticism and contemporary British fiction and teaches English literature at the University of Amsterdam and HAN University of Applied Sciences.

In this series of posts, Astrid Bracke writes about the process of moving from disseration to book. She has a PhD in ecocriticism and contemporary British fiction and teaches English literature at the University of Amsterdam and HAN University of Applied Sciences.

While every publisher has their own book proposal guidelines – available on their website – these tend to cover the same elements, such as the title, short summary, a longer chapter-by-chapter outline and a section on the significance of your book. Some publishers ask you to fill in a form that covers all of these elements, and others simply require you to submit a document that incorporates all the required elements in a running text.

An obvious but nonetheless worthwhile piece of advice is that if a publisher suggests a certain structure, follow it. While you may feel that deviating from the requested structure reflects originality and individuality, the editors and reviewers that will evaluate your proposal are used to a certain structure. Choosing a different structure will more likely confuse or even irritate the editors and reviewers – who usually have little time – rather than make your proposal stand out positively.

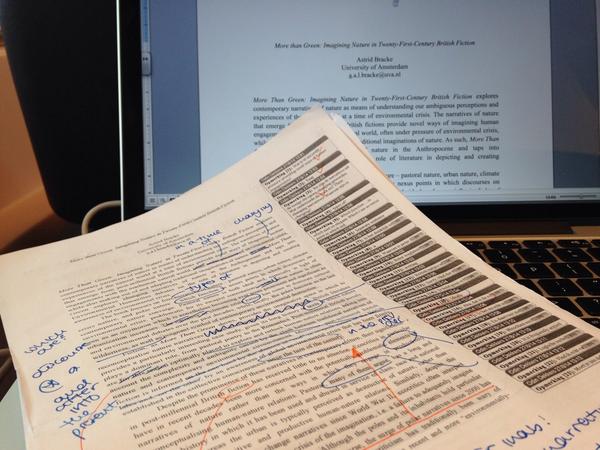

When I started working on my book proposal, I found it nonetheless hard to determine what my book proposal should look like. Asking a friend who works more or less in the same field as I do whether I could look at her – successful – proposal helped me a lot. Another valuable resource is Palgrave Macmillan’s Open Peer Review Trial. Although primarily meant to encourage open peer review of submitted book proposals, its archive gives examples of book proposals and the feedback they received.

Eventually I decided to write a proposal as a running text that includes the elements that most publishers require. This allowed me to really conceive of my proposal as a whole, rather than a series of fields to be filled in as part of a form. Once I’d written the proposal – and had asked feedback from trusted colleagues – I could tweak and adjust the proposal to the specific forms or guidelines provided by individual publishers.

I structured my proposal as follows:

-

A longer section describing the book’s main argument, the gap(s) it will be filling and the texts and theories I’ll be concerned with. This section ends with a paragraph that sums up the specific contributions the book will make (total length about 6 paragraphs);

-

Table of contents with titles of chapters and word count. Includes notes and bibliography;

-

Chapter outline (about 500-650 words per chapter);

-

Market;

-

About the author;

-

Timeline for completion.

A number of these elements are particularly important, and worth thinking about some more.

First, you’ll need to demonstrate the significance of your book. Why should others read it? What does it contribute, and to which fields? This may require you to broaden the scope of your dissertation somewhat. The challenge is to turn your dissertation from something that is interesting primarily to your supervisor and committee members into a book that will gain the interest of a larger group of scholars.

For instance, my dissertation was aimed explicitly at expanding ecocriticism through readings of contemporary British novels. While this may be of interest as well to some scholars working outside of ecocriticism, my primary audience consisted of ecocritics, and I explicitly engaged with and responded to existing work in the field. In order to appeal to a wider audience – and hence make the book more interesting to publishers – my monograph is less explicitly concerned with ecocritical theory and practice. Instead, I’ve shifted my focus to the second element of my dissertation: an analysis of representations of nature in contemporary fiction. Since my own interest as well as work in the field is moving towards post-millennial British novels, I’ve adjusted my corpus from novels published between 1975 and 2011 – as was in the case of my dissertation – to British novels published since 2000. Consequently, the audience for my monograph increases, as I aim to appeal to several scholarly communities equally: ecocritics as well as those working on contemporary fiction, especially post-millennial British fiction.

In the next post I’ll discuss another key element of the book proposal – the market section – and one of the most frequently heard pieces of advice for recent PhDs: making your book sounds less like the dissertation you based it on.

Leave a reply