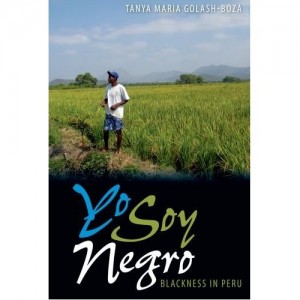

Today’s post written by Tanya Golash-Boza is her second blog post for PhD2Published (see her first, very popular post about writing a peer review here). Here she reflects on her experience of publishing a book from her dissertation, providing particularly useful insights into the publishing process.

When I finished my dissertation, I knew I wanted to transform it into a book. I did not, however, know anything about the publishing process. As I am now finished with this long process, this is an ideal time for me to outline the steps so that others can know how to publish a book from your dissertation. In this blog post, I will explain the book publishing process. However, keep two things in mind: 1) there is a lot of variation beyond what I describe here and 2) this is generally the process for the first book, not necessarily for the second or third.

Step One: Write the Book Prospectus

Although it seems daunting, a book prospectus is not a complex document. I describe the book proposal in detail here. Briefly, it contains: 1) a summary of your book that outlines the main argument; 2) a one-paragraph summary of each chapter; 3) a timeline for completion of the book manuscript; 4) a brief description of the target audience and potential classes for course adoption; and 5) the competing literature. Usually these are short documents. Mine have ranged from four to seven single-spaced pages.

Step Two: Submit the Book Prospectus

The second step is to find a press that might be interested in your book manuscript and to send them a book prospectus. I explain how to find a press here and how to contact the aquisitions editor here. Once you have selected the press and found out the name of the acquisitions editor, you can send them the prospectus. Often, the press also will want one or two sample chapters. You can send your prospectus to as many publishers as you like. Most publishers list submission guidelines on their websites. These guidelines often indicate exactly what materials they would like to see: usually a prospectus, one or two sample chapters, and a two page CV.

Step Three: Submit the Book Manuscript

When acquisitions editors receive your prospectus, they make a decision as to whether or not they will send your book manuscript out for review. If they do not, they will send you a letter with their regrets. However, if they are interested, they often will call or email you with a request to see more materials. Some presses want to wait for the whole book manuscript to be completed. Others will send out just the prospectus for review. Others will send out 1-4 finished chapters. That depends on the book and the press. They will let you know.

Step Four: The Press Sends Your Manuscript out for Review

You wait between one and twelve months for the reviews to come back. If just the prospectus is under review, this will not take very long. If it is the whole manuscript, usually you will wait several months.

Step Five: You Get a Contract

The press makes a decision based on the reviews. They can decide to a) offer a contract based on the reviews; b) ask you to do more revisions and send it out for review again or c) decline to offer a contract based on the reviews. If it is c), you go back to Step Two.

Step Six: You Sign a Contract

If the reviews are favorable, the press will offer you a contract, which you first negotiate and then sign. Here are some items often up for negotiation: 1) who will pay for the index; 2) who pays for the cover and inside pictures; 3) who pays for the copy-editing; 4) the royalties rate; and 5) when and whether the book will be released in paperback. You may or may not be able to negotiate these items, but it does not hurt to ask.

Step Seven: You Revise the Manuscript

You revise the manuscript based on the reviews. Some presses will send it out for review again once you revise it. Others will review it internally and ask you to make further revisions. Still others will send it as is to the copy-editor after you make your revisions.

Step Eight: Copy-Editing

Once the book manuscript is revised, it goes to the copy-editor and they proofread the text. This usually takes 1 to 3 months.

Step Nine: Revision

You revise it again, based on the suggestions made by the copy-editor. You then send it back to the copy-editor who sends it to the press after your final approval. You usually have one month to respond to the copy edits.

Step Ten: Page Proofs

Your book is put into page proofs that you get to read and revise again. At this stage, however, you can only make very minor changes. You correct any mistakes and then it goes to the printer.

Step Eleven: In Press

The page proofs are sent to the printer, and you wait for your book to be printed. Printing usually takes a couple of months.

Step Twelve: On the Shelf

Your book is available for sale! Now that your book is for sale, be sure to include a link to the publisher’s website or to Amazon.com in your email signature to advertise your book.

As made clear in these twelve steps, publishing an academic book is often a very long process. It is important to keep in mind that it can take years to publish a book, even after you have completed the manuscript.

For example, I completed the manuscript for my first book in May 2009 and sent it to a publisher who had agreed to review it. I received the reviews in November 2009, and the publisher offered me a contract on the basis of the reviewers’ evaluations at that time. I signed the contract and then revised the book according to the suggested revisions and returned it to the publisher in March 2010. In June 2010, I received and reviewed the copy-edits. In October 2010, I received and reviewed the page proofs. The book was released in February 2011 – nearly two years after I had originally “finished” the book manuscript! Keeping this timetable in mind is particularly important if your university prefers you to have a bound book when you go up for tenure.

Melanie Boeckmann, M.A. works as Research Fellow at the University of Bremen and pursues a PhD in Public Health at the Leibniz Institute for Prevention Research and Epidemiology – BIPS in Germany. You can find her on twitter @m_boeckmann.

Melanie Boeckmann, M.A. works as Research Fellow at the University of Bremen and pursues a PhD in Public Health at the Leibniz Institute for Prevention Research and Epidemiology – BIPS in Germany. You can find her on twitter @m_boeckmann.

(C) Follow These Instructions http://www.flickr.com/photos/followtheseinstructions/

(C) Follow These Instructions http://www.flickr.com/photos/followtheseinstructions/