Todays post is written by Helen Wainwright. Helen is a final year PhD Candidate from The Department of Art History at The University of Nottingham, researching conceptual art’s supposed demise in the early 1970s in New York, and the concurrent redefinition of the spaces and/or places of artistic practice and dissemination stemming from the period. She is particularly interested in the work three separate artists: Stephen Shore (1947-present), Gordon Matta Clark (1943-78) and Anthony McCall (1946-present), and the gap that exists between their early works and later (re)interpretations of them.

Todays post is written by Helen Wainwright. Helen is a final year PhD Candidate from The Department of Art History at The University of Nottingham, researching conceptual art’s supposed demise in the early 1970s in New York, and the concurrent redefinition of the spaces and/or places of artistic practice and dissemination stemming from the period. She is particularly interested in the work three separate artists: Stephen Shore (1947-present), Gordon Matta Clark (1943-78) and Anthony McCall (1946-present), and the gap that exists between their early works and later (re)interpretations of them.

Twitter: @adxhw1

http://nottingham.academia.edu/HelenWainwright

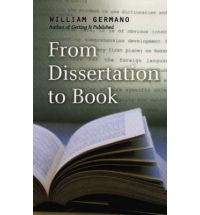

Recently, the thoughts of what to do post-PhD have started to worm their way into my mind – a good six months ahead of schedule. Rather than ignoring my subconscious efforts to prompt me into a premature job search, I used them as a nudge in the right direction to think about what I really want to accomplish in the year leading up to my viva, and likewise what I would need to accomplish in the subsequent year (or two) after it. This is when I metaphorically stumbled, via Twitter, across William Germano’s book From Dissertation to Book, an extremely useful and accessible text first published in 2005 by University of Chicago Press. I initially approached it with caution, thinking it would ultimately lead to a flurry of self-doubt, but what I actually found was an insider’s guide to what it takes, and how to make the first moves towards publishing your thesis as a book, and what decisions and barriers will more than likely be encountered along the way.

As the Dean of the Faculty of Humanities and Social sciences at Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, and a former Vice President and Publishing Director at Routledge, William Germano knows exactly what it takes to take those first steps towards publication. The message running throughout the book is clear: be willing to revise, rework and even rethink your PhD research. This advice is coupled with a hefty warning: a thesis is not a book manuscript and will more-often-than-not be rejected by a publisher without any form of editing. Germano provides his readers with a list of eight options to choose from when considering what to do with the thesis once complete: ‘do not resuscitate’; ‘send the dissertation out as is…’; ‘publish the one strong chapter’; ‘publish two or three chapters as articles’; ‘revise the dissertation lightly’; ‘revise the dissertation thoroughly’ or ‘cleave the ample dissertation in two’ (p.38). It is safe to say that readers of From Dissertation to Book are most likely seeking advice on just that topic, and are thus left with the sole prospect of gentle/hefty revision. However, reading between the lines, I think the underlying message of the book is clear: there are more routes towards writing your first book than simply turning your doctoral dissertation straight into a manuscript.

One suggestion is the transformation of chapters into publications. Not only will this allow ideas to be transmitted to a larger audience; gaining much needed publicity, but it will grant the opportunity for a moment’s pause to deliberate whether these ideas could actually form the basis of further research, and lay the foundations for an entirely different book proposal. Likewise, such reflection may aid in the dissection of the thesis as a whole; allowing it to be sliced in two, moving both parts in separate directions, and therefore furthering the possibilities of future research and publication. Alternatively, as Germano continually recommends: revision is the key. Whilst attempting to re-work the thesis, it is also highlighted that a publisher who can recognise the potential audience for a book is far more likely to accept a manuscript or proposal, because they can clearly see who the text is aimed at and who it will be sold to. In contrast to the doctoral thesis, which will only ever meet the eyes of a handful of people, despite best wishes, the book must have a definite audience, and therefore a direct and highly relevant message. If you can argue this case straight away, then perhaps you are on to a winner.

The awareness of your thesis as something far from finished, but as the stepping stone into the world of academia is a daunting prospect, given the amount of blood, sweat and tears which are poured into the work. However, this realisation is also entirely invigorating when realisation dawns that all the routes of thought that had to be closed off in order to concentrate on getting to the finish line, could one day be re-opened. As a researcher you are expected to be adaptable and full of belief in your ideas, and From Dissertation to Book echoes these basic assumptions, asking its readers to think in the same way about their doctoral research: that it is malleable and full of potential, whether published as a book on first attempt, or not.

(C) http://www.flickr.com/photos/james_scott/

(C) http://www.flickr.com/photos/james_scott/

(c) Moyan Brenn Berkut83@hotmail.it

(c) Moyan Brenn Berkut83@hotmail.it

http://www.flickr.com/photos/smithsonian/2422570279/

http://www.flickr.com/photos/smithsonian/2422570279/