Writer. Dancer. Tea Drinker. Idea Wrangler. See more of Dana’s work and writing at www.danamray.com

Writer. Dancer. Tea Drinker. Idea Wrangler. See more of Dana’s work and writing at www.danamray.com

Congratulations! You are just a few days from the end of Academic Writing Month. It has been a remarkable amount of work and effort. Perhaps you made all your goals. I have a confession: I struggle to meet goals. Rarely do I set a word or page count to meet and then actually follow through. Sometimes, that makes me feel like a failure. But the process profoundly challenges me to push into new terrain in the composition and drafting processes. My writing can improve trying to meet new goals even when I fail to meet them; trying to run a mile helps even if we huff and puff and walk most of the way.

Often, it is the process itself that is illuminated and gives the best take-aways from a month like AcWriMo. My words might be weak on the page but I have learned new skills and tools to keep pushing forward with writing.

Trying Scrivener has been a useful lens on my writing process in a deeper way that I had reason to consider before. Years of using Microsoft Word make the first drafting steps seem familiar. Familiarity can trigger all the old habits and hang-ups and anxieties before the first word is even in the document. There are things that a new, shiny tool cannot solve: drafting aversion, anxieties, stress shut downs, revision nightmares, etc. Fundamentally, Scrivener cannot solve the person demons and hang ups that we each carry into the lonely process of drafting. But Scrivener, or other alternative writing tools, can thwart what we expect in the first writing moments. With an altered first step, we have the chance for a new outcome.

Scrivener, as a new and unfamiliar writing space, made it easy for me to notice some of my quirks, like the myriad of ways I dart to distraction instead of drafting. Writing can be an anxious process for me. I have had to face my fears about writing in a new way than I had before. I have had to face the things that prevent me from sitting down and getting the work done.

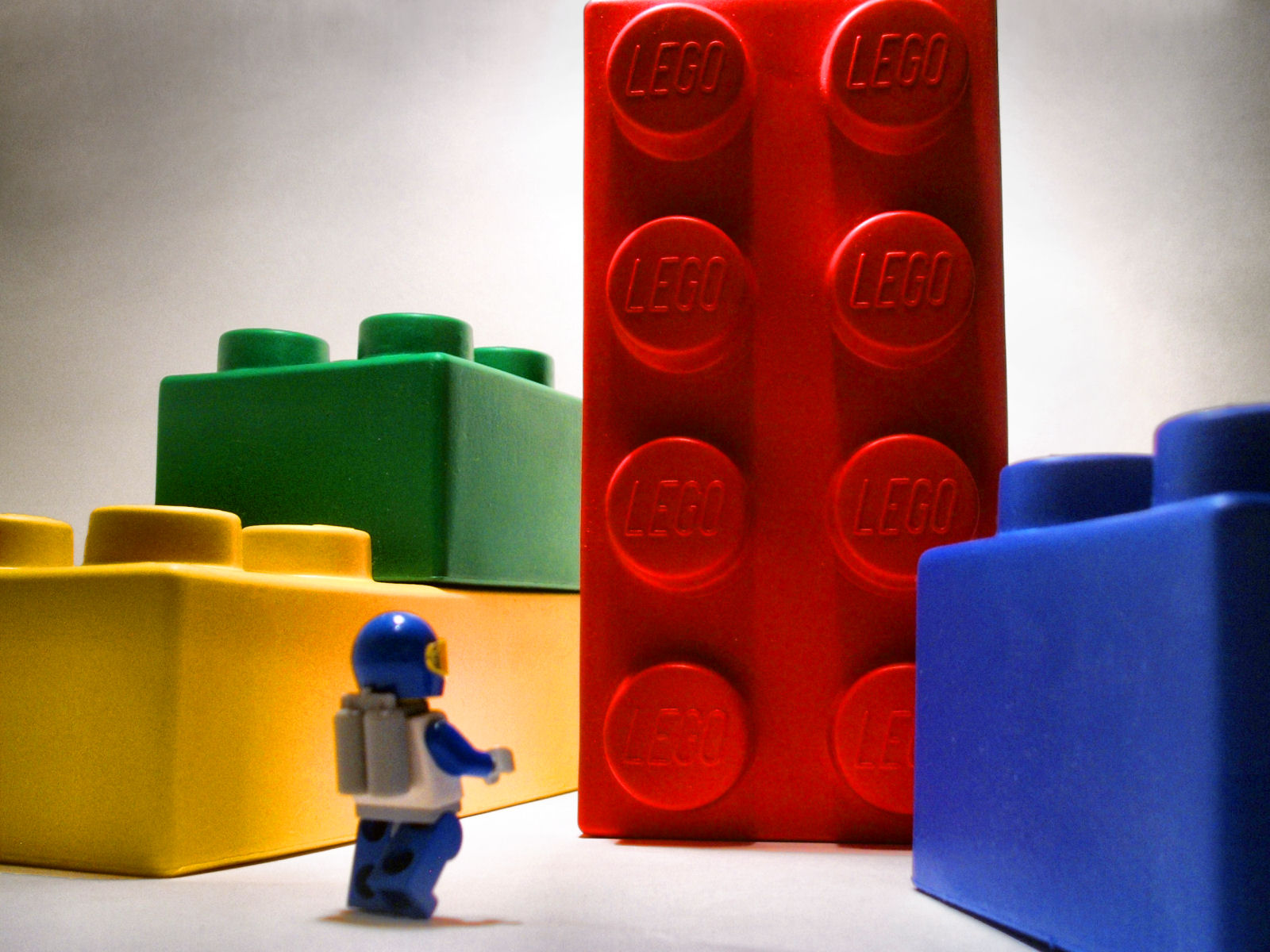

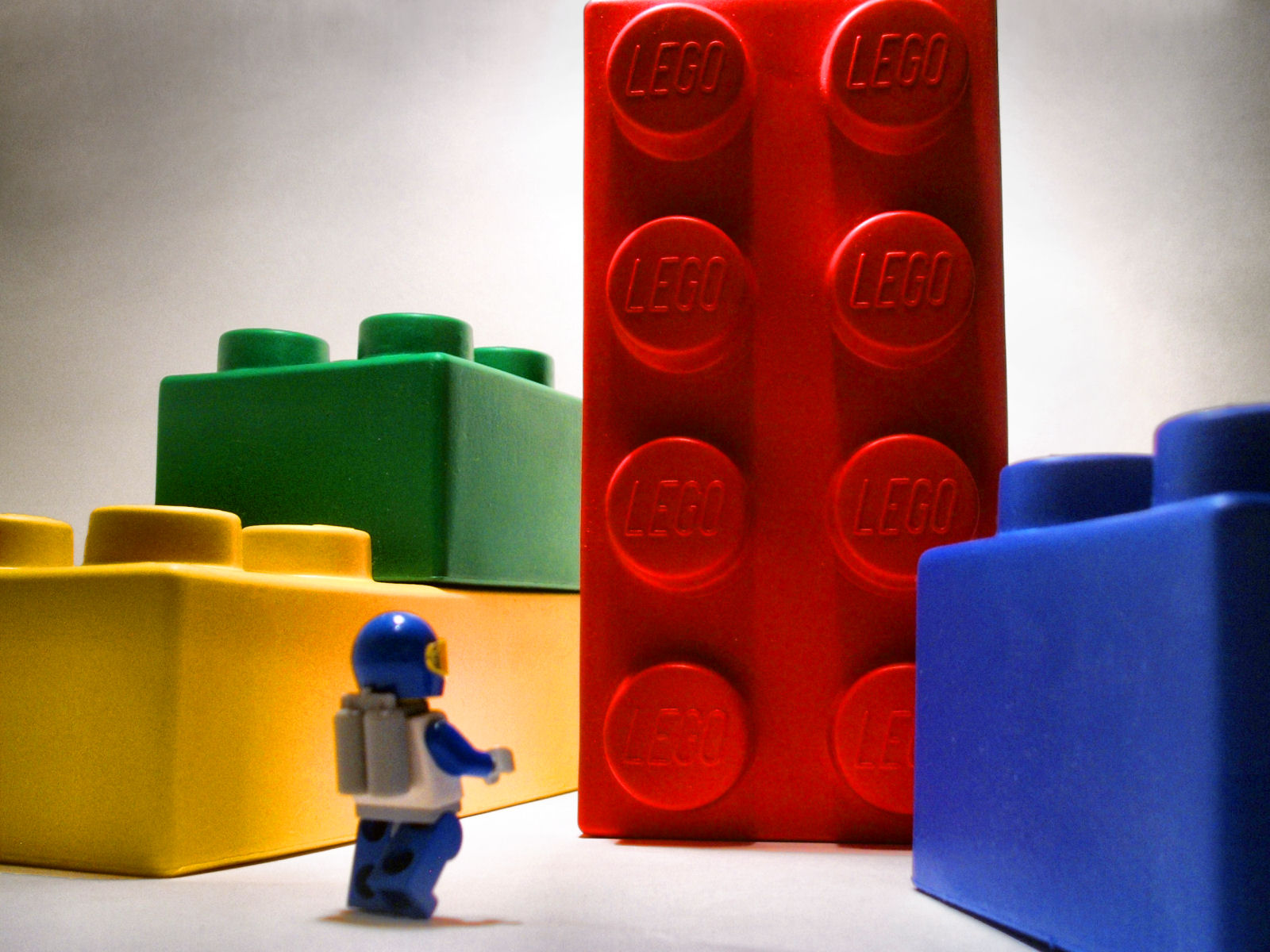

In conclusion, Scrivener did not become my new best friend. But any new tool, if we give it the chance, can jolt us out of our detrimental habits. New tools can shine a little light on the more miserable parts of our inner academic world, the difficult places where the shiny ideas and associations that got us into scholarship are not as alluring as they once were. Recognition is the first step toward addressing the far more difficult inner work that a new tool cannot ever solve. Tools are only as useful as we make them. It takes time and discernment and some messing around (and the Longest Tutorial) to figure out what works for us.

I raise a glass to you for your hard work! To Scrivener! To our tools old and new and to all the light they shine!

Summary of my favorite parts of Scrivener:

- Pin board. The ability to shift sections of text around in the document by looking at the note card visual of a project.

- Zen mode. Cut the distractions and get ‘er done.

- Integrating media with the writing process.

- Words not pages. Okay, truth be told, I hated this because the pages make me feel like I got somewhere instead of infinite incompleteness. But shifting my measure of success really impacted my conception of the writing process.

- Potential for creative and scholarly work existing in the same project board.