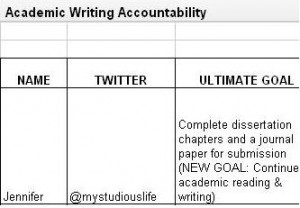

In the second of two posts about Writing Accountability (the first of which introduces the initiative and you can read about here), Jennifer Lim explains how writing progress can be effectively measured and managed. Jennifer’s post is part of PhD2Published’s new Academic Writing feature.

For accountability to work, measuring and monitoring progress are essential too the writing process. Monitoring your own progress helps in recognizing current productivity status and finding ways to improve it. Setting an ultimate goal and daily writing plan to achieve it is important for improving writing productivity. Progress measurement is of great interest to me. As there is no strict rule about how writing progress should be measured, in the Writing Accountability initiative, I find it amazing that everyone has different ways of measuring their personal progress. Here are some examples of how to measure writing progress in order to develop accountability.

Word Counts/Targets

Although some measurements are similar, there are still many different ways of doing it. The most practical method is word count. Whether the final writing achievement is a few thousand words of an article or more than 10,000 words of a dissertation or thesis, word count is the best way to measure and monitor writing progress towards an ultimate writing goal. It is also best to break down the ultimate writing goal into smaller daily goals. Let’s say you need to write at least 12,000 words in 6 months and that most probably you do not plan to write over the weekend. This equates to at least 100 words per day in order to achieve 12,000 words in 6 months. By having this daily writing goal of 100 words, you have a clearer writing plan to help to achieve the ultimate goal and can diminish the overwhelming feeling that a larger word count often creates. If writing 100 words a day is too easy, set it higher or to a limit that you feel is challenging enough to motivate you to write daily.

Time Measurement

Writing is not the only thing one does as an academic however. A lot of time is also spent on reading, making notes, data collection and data analysis etc. Should we not measure those that actually contribute too the final product of our writing? What is the best way to measure these? I personally think the daily time spent on these activities should also be considered. This helps to minimize the feeling of unproductiveness if no significant words are written on those days when other academic activities take precedence. So, another good way to measure daily progress is the total time spent. Set a minimum time that you are willing to spend on a daily basis to work on your academic activities, including reading, literature review, etc. Your time target should be reasonable and something that you can achieve such as 1 or 2 hours a day. Setting a target too high will only decrease your motivation if you can’t achieve any at the end of each day.

Combining the two

It is viable to combine both word count and time spent measurements as the daily goal. In that way, you can measure word count when you are writing and time spent when you are working on other relevant academic activities. I also find it is beneficial to record daily progress together with some comments about what has been achieved or lack thereof so reflection is possible for self improvement. Another example of measurement is from Sarah Ford (who Tweets as @Sarah_M_Ford). She has a unique formula of calculating ‘score’ to measure her daily progress (learn more about it here).

Other than using the spreadsheet for progress update in writing accountability, there are also some #AcWri enthusiasts who like to blog or tweet about their writing goals and progress. The #AcWri community on Twitter provides great peer support where people are sharing writing advice and encouraging one another in the writing process. If you work better with pressure, the #AcWri community can also act as (positive) peer pressure. Seeing others progressing well when you are not provides encouragement to improve your own productivity. Either way, participating in the #AcWri community will only benefit your progress and increase your motivation. Knowing you are not alone in whatever obstacles you are facing provides good solace. The key to accountability is: knowing what you need to achieve and making sure you put in the effort to achieve it. Regardless of how you measure your progress, all you need to do is to find the best way to achieve the ultimate goal by setting targets that are reasonable and achievable.

A brief note from Anna: Being Managing Editor of PhD2Published has been a fantastic opportunity for me so far. It has introduced me to lots of interesting people and has helped me to think about key issues I am facing post-PhD. My current thinking is about whether or not to make my PhD thesis more readily available online. This post, which is the first in a series, explores this idea in more detail.

A brief note from Anna: Being Managing Editor of PhD2Published has been a fantastic opportunity for me so far. It has introduced me to lots of interesting people and has helped me to think about key issues I am facing post-PhD. My current thinking is about whether or not to make my PhD thesis more readily available online. This post, which is the first in a series, explores this idea in more detail.

Impact has increasingly become an academic buzzword and requirement, which has led me to think much more about my PhD thesis, its accessibility and the impact it could (and should) have on a variety of audiences, both academic and public. I have heard from several colleagues that the only people who are ever likely to read the actual thesis are yourself and your supervisor (my family and friends certainly haven’t read it!). Frankly this seems wasteful and a bit sad (just look at the picture!), especially considering all of the hard work that went into it, including by myself, my participants and my supervisors. Even with the potential of developing publications and monographs from it in different formats, later on, in its unpublished form, my thesis is meaningful to me and took time and effort to construct.

This thinking prompted me to consider how I could make my thesis more accessible and more widely read, particularly in an age of social media and open access. Before launching into making it available online however, I wanted to do some research into the potential barriers to publishing online and the current debates that will inform this decision.

Following these musings, I posted this question on Twitter: “What are people’s opinions on making theses available online?” Several interesting and important issues and questions were raised. While limited, there is already an emerging debate about the digital dissertation, which you can read about in this interesting and informative post by Alex Galarza for @GradHacker. There are several positives for doing this, and indeed many universities are now making it a requirement, if it isn’t already. @Gradhacker outlines that online material such as the unpublished thesis for example is still protected by copyright, useful to know if there is concern about the acknowledgement of your work. At the same time, in being overly cautious about protecting your thesis/dissertation you may risk restricting the development of your academic identity, online and otherwise. Furthermore (and some publishers may vary on this) putting your thesis/dissertation online may actually aid in the communication and appeal of your research to a variety of audiences and may even encourage sales of subsequent published work should you wish to publish it elsewhere in a different form. Twitter follower Christina Haralanova (@ludost11) has also received positive replies from people who have read hers.

Despite the many positives, I still think it is important to consider the range of different issues relating to putting a PhD thesis out there; issues that I will explore in a short series of blogs that will be posted here on PhD2Published in the coming weeks. These include posts I have constructed myself, and also opinion posts, and feedback from academic publishers. If any of this resonates and you have anything to add that has occurred to you, please do get in touch, either by Email or Twitter (@PhD2Published). Should you wish to join an online discussion on Twitter about the debate please use hashtag thesisonline (#thesisonline).

WRITE A CROSS-OVER BOOK. Professors build their reputations by publishing articles and books in their specialty. Almost always, their only readers are other professors, graduate students, and their own family. Sometimes, however, a faculty member produces a successful crossover book, a work respected by, and receiving laudatory reviews from, his or her academic colleagues while also selling well with the general public.

WRITE A CROSS-OVER BOOK. Professors build their reputations by publishing articles and books in their specialty. Almost always, their only readers are other professors, graduate students, and their own family. Sometimes, however, a faculty member produces a successful crossover book, a work respected by, and receiving laudatory reviews from, his or her academic colleagues while also selling well with the general public.

Such books are difficult to write, however. If your book is to fly off the shelves at bookstores such as Barnes and Noble, it has to be both readable and entertaining. Few people reach the level of clear and creative writing required. Furthermore, even among highly skilled professional nonfiction writers, New York Times best sellers are rare. Nonetheless, some university scholars have written best sellers. They include Peter Drucker, Margaret Mead, Paul Krugman, Gail Kearns Goodwin, and Stephen Hawking. We believe that professors who produce crossover books perform a valuable public service. Unless you become a world-class public intellectual like the people in the above paragraph, you may be denigrated by your academic peers as a mere popularizer. A false equation that does not work mathematically, but still describes the behavior of many misguided professors: excellent technical productivity plus commercial success is respected less than excellent technical productivity alone.

Following on from my appearence on the panel at RGS Postgraduate Forum – Annual Conference Training Symposium (PGF-ACTS) last week I present the first of three posts from the speakers on publishing. Todays post looks at writing and academic book and is brought to you by Professor Kevin Ward. Kevin is Professor of Human Geography at Manchester University and has been the Editor of Area a journal published on behalf of the Royal Geographical Society (with The Institute of British Geographers) since 2010.

Following on from my appearence on the panel at RGS Postgraduate Forum – Annual Conference Training Symposium (PGF-ACTS) last week I present the first of three posts from the speakers on publishing. Todays post looks at writing and academic book and is brought to you by Professor Kevin Ward. Kevin is Professor of Human Geography at Manchester University and has been the Editor of Area a journal published on behalf of the Royal Geographical Society (with The Institute of British Geographers) since 2010.

So, you’ve decided that you are going to write an academic book. Well, here are five tips:

1. It is worth considering the sort of book you want to write. Look at publishers’ websites and consider the following:

– Does the publisher produce the type of book that you want to write in your field?

– Are hardback and paperback versions of the book published simultaneously? If not, how many hardbacks does your book have to sell before the publisher will commission a paperback run?

– What marketing and distribution system does the publisher have?

– Does the publisher send out copies to academic journals for review?

– Does the publisher attend large academic conferences and participate in book exhibitions? Read more

Today’s post comes from Dr. Claire Warden and considers how to spend your time while moving from PhD to published. Claire is a Lecturer in Drama at the University of Lincoln. Her first book, British Avant-Garde Theatre is out with Palgrave next year. You can follow Claire on twitter here.

Today’s post comes from Dr. Claire Warden and considers how to spend your time while moving from PhD to published. Claire is a Lecturer in Drama at the University of Lincoln. Her first book, British Avant-Garde Theatre is out with Palgrave next year. You can follow Claire on twitter here.

While commenting on a draft copy of my book, my wonderfully generous proof-reader made me rethink my use of citation with the following soupçon of wit:

“Quite a lot of references to what other scholars are doing. Sometimes these get rather too close to the ‘as Dr Dryasdust has said, “Shakespeare lived before the steam-engine”’.

The point being, citation in a book is substantially different from citation in a thesis. Dr Dryasdust’s comment is factually correct but we do not require the good doctor to tell us! And this gets to the crux of the difference between a thesis and a book: the former is written for examination, the latter is written to be read.

The humorous comment also points to a broader issue: the PhD-to-Book process is one of learning, personal development and transforming the way you write. While I completed my PhD in 2007, my first book will only hit the shelves (or shelf on my less ambitious days) next year. This might seem like a large gap and, as I finish the final draft, it certainly feels as if I have spent half a lifetime on it! But, as the story above shows, there is merit in taking your time over this process. There is a great deal of useful material on this site about the PhD-to-Book process, so what I want to do is focus on what to do while you’re waiting. Obviously honing our writing skills and ignoring Dr Dryasdust’s unnecessary interruptions are vital, but what else can be done? Read more

This weeks Top Tips are from Sarah Cook co-author of Rethinking Curating: Art After New Media

This weeks Top Tips are from Sarah Cook co-author of Rethinking Curating: Art After New Media

Publishing can be a waiting game, while you wait to hear if a publisher is going to accept a proposal or not, and then, hopefully, while your manuscript is being peer-reviewed.. Here are some tips (noted with the benefit of hindsight) for how to manage that waiting game.

1. When your dissertation is finished, don’t immediately publish all the best bits in the first invitation you get to contribute a chapter to another book, in case you later get the chance to write your own book! You don’t want to have contractually signed away the first-publishing-rights to that researched material and then have your own book proposal accepted at another publisher. This happened to me. If you do get asked to contribute a chapter to someone else’s edited anthology or journal of course do it, but pick a single idea from your thesis, or a single chapter (not the conclusion!) and rework it accordingly. Read more

This weeks authors tips come from Verina Gfader, author of ADVENTURE-LANDING a compendium of animation, Berlin: Revolver Publishing, 2011

Top 5 Tips for Getting Published:

1. Don’t wait too long to approach publishers after completion. If you consider a later publication choose one which also includes post-doc research.

2. What’s your preferred publisher? Try them first.

3. Before that, identify what the book will be about? What kind of publication? Who is the reader/audience?

4. Think about funding! (essential), identify possible funding bodies, sponsors

5. Do you “need” the publication? It takes a lot of time. Think about what you want to do, career-wise

This is a great guest post from artist and academic Nathaniel Stern on his approach to pitching his thesis as a book.

This is a great guest post from artist and academic Nathaniel Stern on his approach to pitching his thesis as a book.

Nearly 2 years after I submit my dissertation, I finally sat down this Summer to work on my book proposal. I cut my longest chapter entirely, reworked the thesis to be more in line with where the current interests are for my field, and did some overall structural editing that followed suit. I then read several new books from publishers I had been interested in, even penned a few book reviews, before deciding on whom I would approach first, and the “angle” I’d go with.

Like with the original dissertation, this research and new writing helped me to rediscover my passion for the text, as well as to figure the new directions necessary. Here are a few tidbits I think may have helped me: Read more

This week we’re offering some publishing tips from Jussi Parikka, author of Digital Contagions and the forthcoming Insect Media:

This week we’re offering some publishing tips from Jussi Parikka, author of Digital Contagions and the forthcoming Insect Media:

1. To get published, the first thing you should get right is actually have something good to publish. In other words, write a good book. Sounds banal, I know, but when starting your PhD keep in mind the possibility that it is going to be a book one day and try to use that as motivation for your writing. In some countries (such as Finland) this is easier because your thesis needs to be published as part of the PhD process. As s a result, we already tend to think of them as books – which is also part of the reason why they are much more extensive than Anglo-American PhDs. Excitement in what you write about shows comes across to readers well! Read more

This week, Bruce Wands, author of Art of the Digital Age (Thames & Hudson) and Digital Creativity (John Wiley & Sons, Inc.), offers us some of his advice on getting published for the first time.

This week, Bruce Wands, author of Art of the Digital Age (Thames & Hudson) and Digital Creativity (John Wiley & Sons, Inc.), offers us some of his advice on getting published for the first time.

1. Do some research on publishers that release books like the one you are planning. They generally have a section of their website for prospective authors and how to submit a proposal. Follow their directions exactly. You’ll generally need to submit some sample chapters, a bio or CV, who the target audience is and who your competition will be. You may need to rewrite the proposal a few times before the publisher accepts your project, too.

2. Position your book for the widest possible audience. Publishers want sales and having a topic that speaks to a small audience won’t go over well when you propose it. Read more

Right, here we go, the next part of our BubbleCow guide to academic book pitching! I hope you managed to complete your homework regarding the subject area(s) of your book, as it will come in very handy now.

Right, here we go, the next part of our BubbleCow guide to academic book pitching! I hope you managed to complete your homework regarding the subject area(s) of your book, as it will come in very handy now.

In the last post we talked about how you need to see your query letter and synopsis as sales documents. And now we are going to look at the structure of a successful query letter.

A query letter needs to be concise and focussed. That said, it should be much more than a simple ‘please read my extract’. Last time, we highlighted the four aims of a query letter, these were to show:

- You understand the marketplace, Your book will fit into their current list,

- Your book will sell enough copies to make it worthwhile printing it in the first place, You, as an author, can support and promote your book. Read more

This week we’re excited to offer a set of ten tips on publishing success from none other than Stan Hayward, who has had over thirty books published ranging from children’s stories to computer systems, as well as numerous projects to his name.

This week we’re excited to offer a set of ten tips on publishing success from none other than Stan Hayward, who has had over thirty books published ranging from children’s stories to computer systems, as well as numerous projects to his name.

…And if you’re confused by the picture , it’s because Stan Hayward is also the creator of Henry’s Cat!

- Keep a note book with you at all times and list ideas as they come

- Have a book template in mind. This is a book that has been published and you would like yours to be similar Read more

This week, Jeff Johnson, author of American Advertising in Poland , offers us some of his own insight on getting published for the first time.

This week, Jeff Johnson, author of American Advertising in Poland , offers us some of his own insight on getting published for the first time.

1. Talk to former professors, your friends, colleagues and any other people you have known in academia about your project. Ask them to share their publishing contacts and any information they may have. The people we know best can often help us a lot, we don’t often ask though.

2. A few weeks before a conference, make appointments with any relevant attending book editors to talk about your upcoming book projects. Have a prospectus for any book projects you are working on and a copy of your CV. Even if an editor isn’t interested in your current project, he/she may want to publish one of your future books. Keep in contact with the editors you meet and always make a point to say hi whenever both of you attend the same conference. Read more

Marianne Coleman, author of Educational Leadership and Management, provides her top tips on how to get published:

Marianne Coleman, author of Educational Leadership and Management, provides her top tips on how to get published:

1. Be absolutely clear about your focus and the main point(s) you are trying to get across.

2. Don’t be too ambitious in what you try and cover. Most people write more than they intend to not less.

3. Do market research on potential publishers. Find out who is likely to publish material in your area and proposed format. Read more