Luc Reid is an author and blogger specializing on habits and motivation found in recent psychological and neurological research. Visit his website for more writing tips, or his Amazon page to see his work. You can also follow him on Twitter (@LucReid).

Luc Reid is an author and blogger specializing on habits and motivation found in recent psychological and neurological research. Visit his website for more writing tips, or his Amazon page to see his work. You can also follow him on Twitter (@LucReid).

Having done the preparatory research or critical thinking for a paper, article, or book, it would seem as though the hard part should already be over. The rest is just putting things you already know or have available into words, something we all do regularly throughout the day. When we enter into the realm of writing, however, often new obstacles appear as though out of nowhere. By understanding these obstacles, we can gain a new ability to clear the path to successfully completing the work.

Below I’ll describe the six most common obstacles to successful writing along with tactics for getting past them.

Emotional conflicts

Why are you doing this project in the first place? Is it something for which you have enthusiasm on your own, or are you doing it because you feel you have to, because a colleague has railroaded you into it, or because you think it’s what someone in your position should be doing?

We all are sometimes faced with projects that we wouldn’t take on if it were entirely up to us, and typically it’s harder to find motivation to complete this kind of work. To improve focus, motivation, and enjoyment for these projects, it helps to list out our personal reasons for getting the project done, along with reasons for not doing it.

It’s important that the reasons we list are our own. For instance, if a senior colleague invites me to collaborate on a paper, my reasons for accepting might have little to do with my colleague’s reasons for inviting me, and could include “cultivate a professional relationship with my senior colleague” and “learn from collaborating with someone whose work I admire.” My reasons for being reluctant might include things like “Will delay work on my own project” or “Have differences of opinion with prospective co-author.”

Once reasons are listed out clearly, it’s easier to make a conscious choice to accept the drawbacks and to pursue the advantages—or to realize that the advantages don’t outweigh the drawbacks and so choose not to pursue the project at all.

Lack of belief

Whether for logical or emotional reasons, it can sometimes be difficult to believe on a gut level that a particular project is even possible. Belief can be undermined by past difficulties; by a long-term pattern of fearing failure; by hesitation about tasks that are new to us; by lack of support from family, friends, or colleagues; by organizational problems; or in other ways. If these concerns aren’t addressed, a continuing lack of belief that the project can be completed will sap enthusiasm and focus, sometimes to the extent that the project fails for that reason alone.

While the factors that can contribute to lack of belief are too numerous and substantial to address here, the essential task when belief is an obstacle is to recognize the reasons for lack of belief and to bolster belief by other means. Some ways of doing this include talking with supportive friends and colleagues, talking to someone who has completed the same kind of project in the past, putting in additional organizational effort, and visualizing a successful result.

Anxiety about the quality of the result

In the same way that it’s sometimes difficult to feel confident that a project can be completed, people are often impaired in their efforts by worries that the end result will reflect badly on them. Sometimes this can be a result of feelings of unworthiness, unfamiliarity with some of the subject matter or tasks, unsupportive comments from others, high stakes, and related pressures. As with lack of belief, it’s important to get clarity on the reasons for any concern about results and to marshal resources that increase confidence. It can also be helpful for this kind of concern to find a person or group who can review the work before it becomes widely available and can either allay concerns or offer constructive criticism.

Inability to focus

If you’re committed to the project and fairly confident that you can produce good results but still have trouble focusing when you sit down to write, your distractions may be internal, environmental, or both.

Internal distractions often include conflicting priorities or lack of a specific identified task to do next. It can help to set aside a specific block of time during which you have decided your writing project is the most important task. If concerns about other things that need to be done arise, a reminder to yourself that you’ve already considered doing other things and have chosen this as the most important task can sometimes help. If you find yourself stopped by not knowing exactly what to do next, shift into organizational mode: identify the tasks and sections involved in your project and put your efforts into ordering and clarifying them. While this kind of structure isn’t always needed, it’s very often much easier to work from an outline or task list than from a pile of notes.

To minimize environmental distractions, try to choose a place to work where you’re unlikely to be disturbed. A library or coffee shop may in some cases be a more productive choice than home or office, both because people are less likely to interrupt you and because you have fewer of your own distractions available.

In many cases it can be helpful to find a place to work where you don’t have ready access to the Internet, although admittedly this is becoming less and less possible over time.

Trouble finding the time to write

Writing is often not assertive in the way other tasks can be. Meetings and scheduled events have time frames during which they automatically occur. Preparation, for instance for a lecture or presentation, tends to have deadlines. By contrast, writing deadlines, when there are any, are often far enough in the future that the project can be delayed much longer than is reasonable or effective.

Finding the time to write, then, requires creating shorter-term deadlines or generating ongoing enthusiasm for the work. The latter approach is especially useful: by visualizing the benefits of completing the work or taking even a few minutes to dwell on the aspects of the project that are attractive to us, we can create situations in which it’s natural and pleasurable to work and make progress. In terms of creating deadlines, it can help to enlist the assistance of someone who is willing to take a look at the work before it’s due for feedback. Another useful technique is to spend time at the very beginning defining tasks and milestones, with deadline dates for each milestone.

Lack of enthusiasm

Natural enthusiasm for a project is one of the strongest means of creating the will to write, so it’s unfortunate that this is often in short supply. Lack of enthusiasm for a project can point to emotional conflicts of the kind described earlier in this article or can simply be an unavoidable feature of work that’s necessary but not a particular favorite.

Some techniques for generating additional enthusiasm include

· Visualizing positive results

· Identifying a specific element of the project you’re looking forward to

· Reflecting on the impact of doing the project well on your career as a whole

· Reviewing the reasons you want to do the project in the first place

· Talking with someone who shares some of your interests having to do with the project

· Identifying changes or additions to the project that could make it more attractive

While there are any number of factors that can adversely affect willpower and drive, the underlying deception is that whatever mental state we’re in now is the real or permanent attitude we’ll have toward the goal we want to achieve. In truth, our mental state is subject to many influences that are under our own control, so that a state of confusion, pessimism, or dread can be replaced by one of focus, anticipation, and satisfaction.

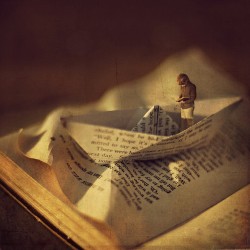

By holyponiesbatman via Flickr

By holyponiesbatman via Flickr

Image by http://www.flickr.com/photos/fiddleoak/

under this licence: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/deed.en_GB

Image by http://www.flickr.com/photos/fiddleoak/

under this licence: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/deed.en_GB