Astrid Bracke writes on twenty-first-century British fiction and nonfiction, ecocriticism, narratology, climate crisis and flood narratives. Her monograph, Climate Crisis and the Twenty-First-Century British Novel, is under contract with Bloomsbury Academic. This is her final post for AcWriMo 2016.

So far in this series I’ve written about the difference between writing a dissertation and writing a book, about planning the book and about the actual writing. In this final post I want to talk about two things: when things don’t go as planned and, related to that, communicating with your editor(s) throughout the process.

So far in this series I’ve written about the difference between writing a dissertation and writing a book, about planning the book and about the actual writing. In this final post I want to talk about two things: when things don’t go as planned and, related to that, communicating with your editor(s) throughout the process.

Although I loved working on the book, around seven months into the process my work life outside of the book became increasingly difficult. Looking back things hadn’t been going well for months: I had struggled with boredom – even though I kept busy – and disinterest in teaching, my colleagues, basically everything. And I just couldn’t stop talking about it: about the things that went wrong, about the things that annoyed me, about the issues that I couldn’t stop thinking about. Sunday evenings became horrible: I’d sit at home stressed and worried about the week ahead. I suffered headaches and a lingering sense of nausea, had nightmares about work, felt tension in my legs and neck, and became much more emotional than I usually am. The turning point came when one day I spent all of a lazy Saturday breakfast with my boyfriend complaining about work, did the same over lunch with a friend, and then over drinks with another friend. By the evening I realized that something was wrong.

This story perhaps really isn’t part of a series on ‘how to write a book’. But at the same time it is. It’s important to me, though difficult, to tell this part of the story. Yes, I enjoyed writing the book, it went well and I am pleased with the result. But at the same time I also ended up having to take a break from writing and suffered from burnout. I know – and I’ve learnt since – that many, if not most, people working in higher education and academia experience extreme stress or burnout at some point. It seems to happen especially to people early in their career. Particularly people in their (late) twenties and thirties experience high levels of work-related stress. What weighs on many of us is the stress of trying to live up to high standards – usually our own.

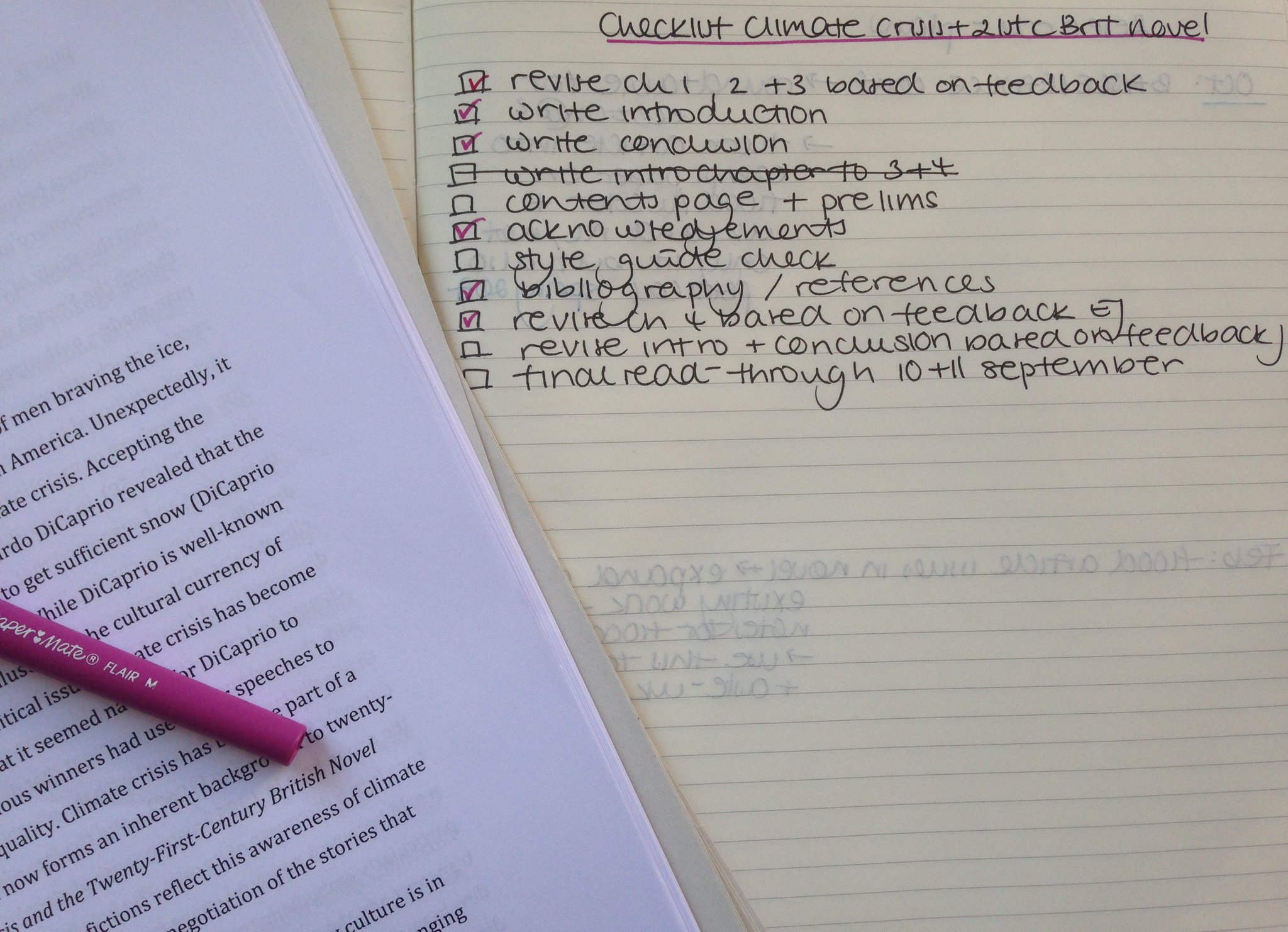

By early May I was off work sick. Even though my burnout was not related to my book, I ended up taking off time from writing as well. Originally I had agreed to submit the finished manuscript to the publisher by the end of July. I was on schedule when I became ill, but had to ask for an extension. Many authors end up needing an extension on their book – either because of illness, because of work obligations or simply because of not being able to finish on time.

It’s important to be realistic when you draw up a plan – either at the beginning of the project or when asking for an extension. No one is served with you making a plan that is too optimistic. If you’ll only be able to submit the book on time if you work faster than you usually do it’s not a good plan. And even when you’ve been realistic in the beginning, things might happen that keep you from finishing on time. Sometimes people don’t communicate, or communicate too late with the publisher. They are ashamed or try to persuade themselves that they could still finish as agreed. This strategy really helps no one and will put you under (even) more pressure. Also, publishers depend on authors delivering their work on time: they draw up publication schedules in advance, and when an author is very late in asking for an extension this can affect the schedule.

Once I realized I had to take a break from writing the book I contacted the publisher and the series editors. I told them I was ill and that I would be unable to deliver the manuscript on time. But I also, importantly, gave them a date on which I thought I’d be done (three months after the agreed date). This was a bit of a gamble: in early May I honestly didn’t know for sure that I’d be feeling better, but with being off work and the summer coming up I assumed that I’d finish the book by the new deadline, September 30th.

It’s been two months now since I submitted the manuscript. It’s currently at the reviewers, with publication set for 2017. The process has been good overall: I enjoyed writing the book, and am generally pleased with how it turned out. At the same time I also had to deal with things not going as planned. What saved me in the end was drawing up a new plan and being clear with the publisher about the delay. And now, all I have to do is be patient for the reviewers’ comments and the published book!

In the previous post I explored the differences between writing a dissertation and writing a book. In this post and the next I’ll write about the process of writing the book, both in terms of practical matters and in terms of deciding on the kind of book you’ll write.

In the previous post I explored the differences between writing a dissertation and writing a book. In this post and the next I’ll write about the process of writing the book, both in terms of practical matters and in terms of deciding on the kind of book you’ll write.