Dr Christopher Hill is a creative writer, who works in the field of academic writing as both a teacher and researcher. Originally from New Zealand, he has spent over a decade living in Hong Kong, Indonesia and Singapore. Chris has a passion for the histories and cultures of the Asia-Pacific region, which form the inspiration for his writing in the form of essays and a novel that is currently in progress. He currently works as a lecturer at the Communication and Language Centre at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore where his research focuses on pedagogical strategies for the teaching of writing. He is currently focused on developing a study investigating the transfer of learning from writing courses to students’ specific disciplines. This is the third of four blog posts he will write for the series. His twitter handle is @chrishillnz.

Dr Christopher Hill is a creative writer, who works in the field of academic writing as both a teacher and researcher. Originally from New Zealand, he has spent over a decade living in Hong Kong, Indonesia and Singapore. Chris has a passion for the histories and cultures of the Asia-Pacific region, which form the inspiration for his writing in the form of essays and a novel that is currently in progress. He currently works as a lecturer at the Communication and Language Centre at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore where his research focuses on pedagogical strategies for the teaching of writing. He is currently focused on developing a study investigating the transfer of learning from writing courses to students’ specific disciplines. This is the third of four blog posts he will write for the series. His twitter handle is @chrishillnz.

It’s the long holiday weekend and everyone is posting their day on Instagram while you are chained to your desk grading your students work. You tell yourself it’s worth it. Your students’ written work deserves your detailed analysis and feedback even if it means sacrificing your holidays.

The day arrives when you finally return said work to your students. You watch in horror, as students glance at the grades on their assignments and then shove them in their bags. Your comments succumb to the darkness never to be glimpsed again.

It was after one such episode that I started to rethink my approach to feedback. Clearly, something wasn’t quite working. Perhaps, my feedback was arriving too late, and maybe what I had to say or how I was saying it wasn’t resonating with my students. I began searching for new strategies for writing feedback. I found inspiration in an article on written feedback by researchers Chris Glover and Evelyn Brown, who point out:

‘Where feedback is given, its prime function is to inform the students about their past achievement rather than looking forward to future work.’

I had always adhered to the traditional model of imparting my “expertise” on students’ work. Before students submitted their work, I would review drafts and offer comments when solicited, but would reserve most of my feedback for after an assignment’s submission.

The idea of reversing this approach and giving feedback for future work rather than past achievements was one that resonated with me. I also had in mind a method which would enable students to take feedback into their own hands, so that it wasn’t just me imparting knowledge, but student’s discovering it for themselves. Finally, I wanted to incorporate blended learning and enable students the flexibility to interact with each other within and without the classroom.

With these goals in mind I hoped that feedback would be less about me defending a grade and more about students learning and engaging as they thought and wrote. I decided to trial these strategies on a first year writing assignment – an argumentative essay by asking my students come up with an argumentative topic in the form of a statement or question and a thesis outlining their position.

The students posted their topics and statements onto the announcement section of our class Blackboard (the online platform not the chalkboard). I asked each class member to give critical feedback to one other student by analysing their topic and statement and assessing whether it was arguable.

Although I chose to use blackboard any online platform would have worked: Canvas, Turnitin, Google docs and Facebook could all be employed for this type of activity. With educational technologies there is no perfect bullet for solving education challenges.

A mistake I made early on with blended learning was to try to fit my classes and goals around the technology. Instead, I now think about how technology can help achieve the learning outcomes I set for the class. In this case, I simply wanted to give the students a virtual space to share and critique their ideas and blackboard served this purpose just fine.

The results of the activity were encouraging. The students’ feedback on each other’s work was insightful and accurate. Colleagues had warned me of the time danger that these type of activities can involve. For example, it can be easy for an educator to lose hours giving feedback on an endless list of comments.

To avoid this, I told the students I would only give them feedback via email if I thought they were off track. I then looked through the statements and the peer feedback comments and identified a few outliers 4-5 students in a class of 25 whose comments or feedback confused or astray and offered some suggestions. I then asked these students to re-post/re-critique afterwards.

An unexpected effect of this trial was that some students put some extra work in and added claims to their topics and statements, and their peers in turn gave feedback on whether these claims were strong or weak and some even come up with counter claims. This was not planned at all, but it got me thinking about how to expand the approach further.

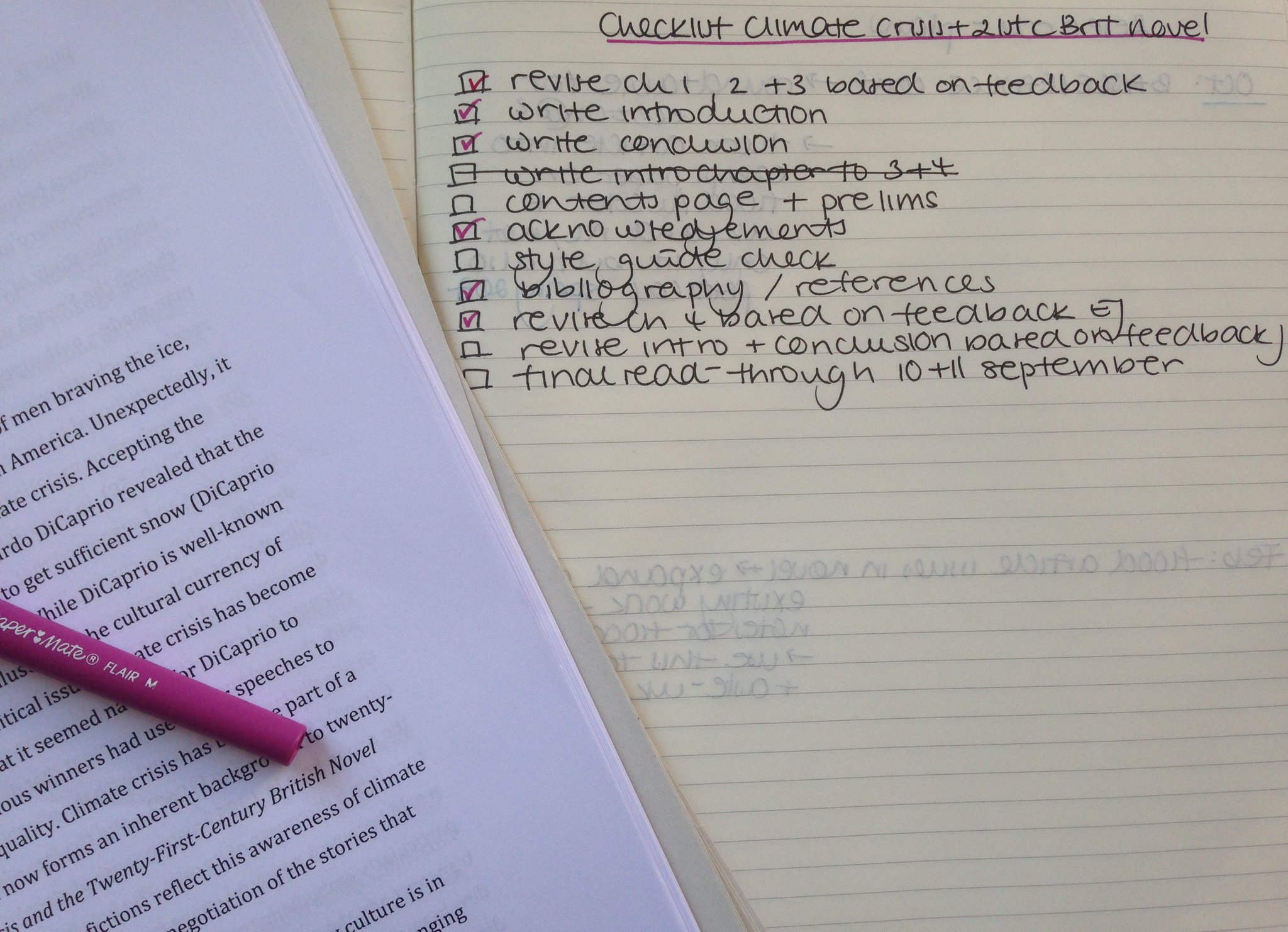

As a result, I am planning to expand the activity, so that it becomes a weekly homework activity in the month running up to the submission date. Students will upload a topic and thesis statement, followed by claims, and then counter claims and brief outlines of examples to support claims. Each week students will offer their peers critiques of these posts, guided by some questions and approaches we study in class. It would also be possible to have students give feedback on entire drafts of each other’s work depending on your university’s policies. To ensure my students stayed motivated I let them know their peer feedback would go towards their class participation grade.

My initial impression of this experiment is that my students have produced better work. Previously, I often had a few students who submitted assignments that weren’t arguable, were off topic or poorly structured. By employing this feedback for future work approach I saw an instant improvement.

The process of giving feedback and working through the stages of writing in steps, also helped to enhance the students understanding of academic writing processes and meant that even if they decided to write the essay at the last minute, a lot of thought and effort has already been put in. They had been critiquing other’s work for several weeks and had been thinking about their own topic, had a clear structure, and in some cases, examples to work from.

This type of activity can be implied to a wide variety of writing contexts simply by thinking of strategies for putting feedback in students’ own hands, making sure that the feedback happens for students’ future work and giving students opportunities to participate both within and without the classroom.

In most cases university policy around the world dictates that there still must a grade and a justification, so no promises that this approach will save your holidays, but possibly at least you can grade with the confidence that your students have already discovered much of the feedback they really need.

Glover, C., & Brown, E. (2006). Written Feedback for Students: Too much, too detailed or too incomprehensible to be effective? Bioscience Education, 7(1), 1-16. doi:10.3108/beej.2006.07000004

After 5 years of busting a gut to produce AcWriMo annually, I (Charlotte Frost) have had to bow out this year. My personal and professional commitments mean it simply isn’t possible for me to organise the content and corral you all into absurd levels of productivity. So I’ve taken the difficult decision of not being the AcWriMo producer for 2017.

After 5 years of busting a gut to produce AcWriMo annually, I (Charlotte Frost) have had to bow out this year. My personal and professional commitments mean it simply isn’t possible for me to organise the content and corral you all into absurd levels of productivity. So I’ve taken the difficult decision of not being the AcWriMo producer for 2017.

In the previous post I explored the differences between writing a dissertation and writing a book. In this post and the next I’ll write about the process of writing the book, both in terms of practical matters and in terms of deciding on the kind of book you’ll write.

In the previous post I explored the differences between writing a dissertation and writing a book. In this post and the next I’ll write about the process of writing the book, both in terms of practical matters and in terms of deciding on the kind of book you’ll write.